Parasha for the Week: Vayikra: Leviticus 1:1 - 5:26.

Haftarah for the Week: Isaiah 43:21 - 44:23.

Apostolic Writings: Mark 1:1 - 8.

Overview

The Book of Vayikra (Leviticus), also known as Torat Kohanim -- the Laws of the Priests -- deals largely with the korbanot (offerings) brought in the Mishkan (Tent of Meeting).

The first group of offerings is called korban olah, a burnt offering.

The animal is brought to the Mishkan's entrance. The one bringing the offering sets his hands on the animal. Afterwards it is slaughtered and the kohen sprinkles its blood on the altar. The animal is skinned and cut into pieces. The pieces are arranged, washed and burned on the altar.

Various meal offerings are described. Part of the meal offering is burned on the altar, and the remaining part eaten by the kohanim. Mixing leaven or honey into the offerings is prohibited.

The peace offering, part of which is burnt on the altar and part is eaten, can be either from cattle, sheep or goats. The Torah prohibits eating blood or fat.

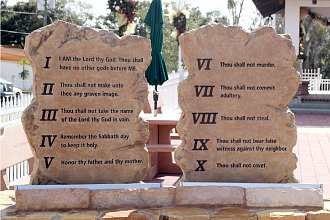

The offerings that atone for inadvertent sins committed by the Kohen Gadol, by the entire community, by the prince and by the average citizen are detailed.

Laws of the guilt-offering, which atones for certain verbal transgressions and for transgressing laws of ritual purity, are listed.

The meal offering for those who cannot afford the normal guilt offering, the offering to atone for misusing sanctified property, laws of the "questionable guilt" offering, and offerings for dishonesty are detailed.

Vayikra: Parasha’s Title

This week’s parasha starts the study the Leviticus; this is the Greek name of this book. The Hebrew name of this book is Vayikra, which is the first word of the book and means: “And he called” the book starts saying: “Now Hashem called to Moses” (Leviticus 1:1). "Leviticus" is an appropriate name, because much of its content concerns the service of the “Levites” in the Tabernacle, the Temple and all the priestly ritual. That is why the Jewish tradition has called this book “Torat Kohanim” (the law of Priests).

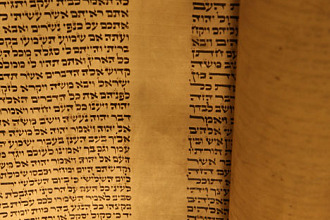

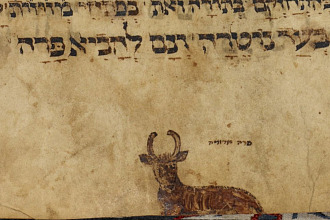

We understand that the word Vayikra is a verb, and in biblical Hebrew the verb is placed first and the then the subject. However, there is a particularity in this first word of this book, the word Vayikra is written with the Hebrew letters וַיִּקְרָ֖א as we can see the last letter which is an Aleph is written in a smaller size than the other letters. Many explanations have been given about this phenomenon. But most of the commentators agree to say that this aleph and its reduced size reflect the humility of Moses.

When G-d told Moshe to write the word Vayikra “And He called”, Moshe didn’t want to write that last aleph. It seemed to Moshe that it gave him too much importance. How could he write that G-d called to him? Who was Moses, after all? A mere man. Moshe would have preferred to write Vayikar -- “And He happened (upon him).” In other words G-d just “came across” Moshe, He didn’t “go out of His way” to appear to him.

In spite of Moshe’s protestations, G-d told him to write Vayikra -- “And He called”. Moshe wrote the aleph at the end of the word as G-d had commanded him -- but he wrote it small. What’s in a small aleph?

The aleph, first letter of the Hebrew alphabet, it is the letter that represents the "will," the "ego." It is the first letter of the Hebrew word “I” -- ‘Ani’ or Anochi. When a person sees himself as the Big A, the Big Aleph, the "Number One," he is usurping the crown of He who is One.

When a person sees himself with humility as "a small aleph," then he makes room for the Divine Presence to dwell in him.

Moshe was the humblest of all men. Moshe made himself so little that he was barely in this world at all. He didn’t even want to be a small aleph. He, as no man before or since, saw that there is only one aleph in all of Creation, only one Number One -- G-d.

Moshe made his own aleph -- his ego -- so small, that he merited that the Torah was given through him.

According to the Jewish tradition, when Moshe had finished writing the Torah, some ink was left in his pen. As he passed the pen across his forehead the drops of ink became beams of light shining from his visage. That extra ink that was left in Moshe’s pen was the ink that should have gone to write the Big Aleph; instead it became a corona of shining light to adorn the humblest of men. (Ba’al Haturim, Midrash Tanchuma).

Korban – Coming Closer

Since the Book of Leviticus includes the details of the sacrificial system, it is important to remember that "sacrifices" are introduced in this way “Speak to the sons of Israel and say to them, ‘When any man of you brings an offering to Hashem, you shall bring your offering of animals from the herd or the flock'" (Leviticus 1:2). There is no word in English, French, or Spanish that adequately conveys the concept inherent in the Hebrew term “Korban,” which is the common word for “offering.” Unfortunately, this word has been used mostly in the sense of “sacrifice.” It has taken on the connotation of destruction, annihilation, and loss -- a connotation that is foreign and antithetical to the Hebrew concept of Korban. Even the original meaning of the Latin word “offero” in the sense of “offering” does not correspond to Korban in its full sense.

The concept of Korban, however, is far removed from all of these; it is never to be understood as a gift or a present. It is found solely in the context of man’s relationship to G-d, and can only be understood on the basis of the meaning of the root “KaRaV.”

The meaning of karav is “to draw closer,” “to arrive at a close relationship with someone.” Thus, korban serves to meet the needs of the one who offers the korban, and not the needs of the One to whom the korban is brought near. The will of the one who brings the Korban is that something of his own should come into closer relationship with G-d. “but your iniquities have made a separation between you and your God, and your sins have hidden his face from you so that he does not hear” (Isaiah 59:2). To come closer to G-d is the very essence of a Korban.

The purpose of a korban is to seek G-d’s nearness “they delight to draw near to God” (Isaiah 58:2), which is good for a believer “But for me it is good to be near God” (Psalms 73:28).

When we understand this meaning of the word Korban, it is also understood that G-d does not demand to be appeased through an offering, in accordance with the blasphemous pagan delusion.

That is why it is not the name Elohim which is associated in the text with offerings, but the name YHWH, this name refers to G-d’s attributes of mercy and love. He appears in the full force of His liberating love, which brings into being all of life, sustains its existence anew, and grants it a renewed future. The essence of an offering is not killing, but rebirth and renewal of existence. Spiritual and moral awakening and revival: entering into a life more noble and pure; renewing strength for such a life from the never-failing source of G-d’s love.

The Leader Who Sins

The bible has laws for everyone in Israel, even the leaders (king, prince, or president) who are not above the laws and must respect them. The Torah states: “When [If] the leader [nasi] commits a sin by unintentionally violating one of the Almighty’s commandments which he should not have done” (Leviticus 4:22). Rashi comments that the first word in our verse “asher” (when or if) is related to “ashrai” which means “fortunate.” Fortunate is the generation in which the king brings an offering when he transgresses unintentionally the laws. All the more so will he regret it if he does something wrong intentionally.

The question arises why the Torah only states this here in reference to the king transgressing unintentionally. Why did the Torah not use this in reference to the High Priest or the Sanhedrin whose sacrifices are dealt with in previous sections of this Torah's portion?

The answer is that the High Priest had a high level of sanctity and the members of the Sanhedrin were great Torah scholars. Therefore, these factors contributed to their regretting the wrongs that they did. However, the king was a person with much power, and power gives a person such high feelings about himself that he is unlikely to admit that he has done anything wrong. For this reason, when the king with unlimited power admits that he has erred and regrets what he has done, it is fortunate for his generation.

Admitting that one has erred takes much courage. The more power that you have the greater the importance of having the intellectual honesty to admit that you have made a mistake. Take pleasure whenever you are brave enough to admit that you were wrong. This pleasure will give you the strength to accept the fact that what you have done was wrong.

Haftara: Isaiah 43:21 - 44:23

The book of Leviticus, which is called Vayikra in Hebrew, is the book that God revealed to Moses in order to teach the priests (kohanim) how to use the sanctuary. In addition of the inauguration of the sanctuary and the dedication of Aaron and his sons, this book is about the sacrifices that Israel had to offer to God for the forgiveness of their sins.

This Haftara of Isaiah is a confirmation that Israel has not been always faithful in her service to the L-rd “You have not brought me sheep for burnt offerings, nor honored me with your sacrifices” (Isaiah 43:23). However, before reproaching to Israel for what is wrong, the text starts with a promise: “The people I formed for Myself, so they might declare My praise” (Isaiah 43:21). God’s people have been formed by God with the purpose of praising Him. Israel praised Him from time to time in the wilderness, but has quickly forgotten Him: “Yet you have not called on Me, Jacob, for you have been weary of Me, Israel” (Isaiah 43:22). And Isaiah continues saying: “You have not brought Me sheep for your burnt offerings; nor have you honored Me with your sacrifices. I did not compel you to serve offerings nor wearied you with incense” (Isaiah 43:23). God gave to Israel clear directions on how to praise Him, how to get forgiveness for sins, and how to worship Him. They have forgotten that it is God and only God who erase and delete their sins: “I, I am the One who blots out your transgressions for My own sake and will not remember your sins” (Isaiah 43:25). Maybe they were contaminated by pagan worship; maybe they accepted pagan concept of God being pacified by their sacrifices, not remembering that the Sanctuary’s sacrifices were not there to pacify the wrath of an angered God. The sacrifices were commanded by God to teach them His love and the ministry of the Messiah who will purify His people: “‘But now listen, Jacob My servant, Israel, whom I have chosen.’ Thus, says Hashem who made you, and formed you from the womb, who will help you: ‘Do not fear, Jacob My servant, Jeshurun, whom I have chosen’” (Isaiah 44:1–2). Yeshurun is an affective name that God has given to Israel. This name is from the root YaSHaR which means “straight” even though Israel is unfaithful God continues to see him as a righteous one, literally “the upright one.”

The Lord is a God of love not a Lord of blood; that is why He is always ready to forgive, to bless His people with His spirit, “I will pour out my Spirit on your offspring, and my blessing on your descendants (Isaiah. 44:3). What a loving God, the God of Israel, a God who always demonstrate an unconditional love for His people.

Apostolic Writings: Mark 1:1 - 8

At the beginning of this study of the book Vayikra (Leviticus), we start the study of the Besorah (Gospel) of Mark. Mark was, according to scholars, the first gospel written. The word Gospel or Besorah in Hebrew means “Good News.” This book is the narration of the Good News of the revelation of the Messiah. In fact the Jewish tradition says that the Messiah is already here among us; he is just waiting for the right moment to reveal himself to the world as the Messiah.

A Parable is given in Sanhedrin 98a to illustrate this thought: It is written that Rabbi Joshua ben Levi met the Messiah at the gate of Rome among the lepers, and asked him “when will you come?” The Messiah answered “today.” Meaning that the Messiah can come at any time, we have just to be ready.

The Besorah of Mark is different of the others gospel. It does not speak about the annunciation, the birth, and the childhood of Yeshua. This gospel starts directly with the ministry of Yeshua, as if he suddenly appeared: “In those days, Yeshua came from Natzeret in the Galilee and was immersed by John in the Jordan” (Mark 1:9).

Scholars have said that the author of this gospel was mark, the disciple of Peter, and since Mark was not a close disciple of Yeshua, it is considered that this gospel was written under the dictation of Peter. It is in fact the gospel according to Peter. In the letter Rabbi Shaul has written to the Galatians, he spoke about his ministry and the ministry of Peter, saying: “I had been entrusted with the Good News for the uncircumcised just as Peter was for the circumcised” (Galatians 2:7). This means Rabbi Shaul was sent to preach the gospel to the Gentiles, while Peter was sent to preach the gospel to the Jews. Thus, this confirms that -- if this gospel of Mark was written by a disciple of Peter, who was a preacher among Jews -- it has been written in the Jewish context in order to introduce Yeshua to the Jews.

Already, in the first century the Jewish people were reading the parashot, according to the tradition. This weekly reading of the Torah was established by Ezra, the scribe, when the Jewish people came back from Babylon to rebuild Jerusalem and the Temple. In a regular year, the Jewish calendar had 48 or 49 Sabbaths (12 months, each month 4 weeks, and from time to time an additional week). This is why the gospel of Mark can be divided in 49 portions, reading a portion each week in parallel with the parashah.

The disciples of Yeshua followed the biblical calendar, which presents the month of Nissan as the first month of the year. That is why we are now reading this gospel from the chapter one; the book Vayikra is read just before Pesach on regular year in Nissan, and on leap year on the additional month of Adar.

The Besorah of Mark starts saying: “The beginning of the Good News of Yeshua ha-Mashiach, Ben-Elohim. As Isaiah the prophet has written, ‘Behold, I send My messenger before You, who will prepare Your way. The voice of one crying in the wilderness, ‘Prepare the way of Hashem, and make His paths straight’ ” (Mark 1:1–3). This beginning of the Besorah is very Jewish; it does not start with Yeshua but with the Messenger that God promised to send before the coming of the Messiah. It is an important part of the messianic prophecies; that is why the Talmud speaks strongly about the one who has to announce the coming of the Messiah. This annunciator is called Elijah the prophet, as Malachi pronounced a prophecy about him “Behold, I am going to send you Elijah the prophet, before the coming of the great and terrible day of Hashem” (Malachi 3:23); however, in the text of Mark, Elijah is not named. Mark quotes two texts of the Tanach even though he attributes both of them to Isaiah. The first text was from Malachi: “Behold, I am sending My messenger, and he will clear the way before Me” (Malachi 3:1); and the second text is from Isaiah 40, “A voice cries out in the wilderness, “Prepare the way of Hashem, Make straight in the desert” (Isaiah 40:3).

Mark knows the teachings of the Bible and the expectations of the Jewish people very well. It is impossible to believe that anyone could be the Messiah, if he is not preceded by his annunciator. This was also the expectation of the disciples when asking their question to Yeshua in the gospel of Matthiew: “The disciples questioned Him, saying, “Why then do the Torah scholars say that Elijah must come first?” (Matthew 17:10) His answer was clear, “Yeshua replied, “Indeed, Elijah is coming and will restore all things. I tell you that Elijah already came; and they didn’t recognize him” (17:11–12).

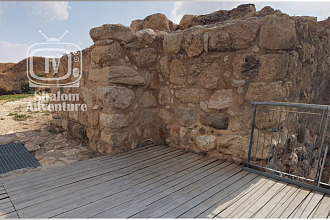

Matthew added his comment: “Then the disciples understood that He was speaking to them about John the Immerser” (Matthew 17:13). John the Immerser is this John that Mark speaks about at the beginning of the gospel “John appeared, immersing in the wilderness, proclaiming an immersion involving repentance for the removal of sins. All the Judean countryside was going out to him, and all the Jerusalemites. As they confessed their sins, they were being immersed by him in the Jordan River” (Mark 1:4-5). This immersion is not something new; it is a very Jewish practice called in Hebrew Tevilah (immersion) in the Mikveh (ritual pool). Everyone who has visited the land of Israel and its old cities and villages such as Qumran, Massada, Jerusalem, Beit Shean, Magdala, remembers that each of these cities have Mikvaoth (ritual baths). Usually, everyone enters the mikveh alone, immerses themselves, and then gets out of it. But here John was immersing people, and before doing it, he asks people to repent. That is why it is written that he was “proclaiming an immersion involving repentance for the removal of sins.” This repentance was necessary because of the coming of the Messiah.

Jewish tradition had a very dark picture of the generation of the Messiah. It is written in the Talmud: R. Nehorai said: in the generation when Messiah comes, young men will insult the old, and old men will stand before the young; daughters will rise up against their mothers, and daughters-in-law against their mothers-in-law. The people shall be dog-faced, and a son will not be abashed in his father’s presence (Sanhedrin 97a). The Messiah was coming; the current generation was a generation of sinners; thus it was necessary to be sure that the people who were immersed knew exactly what they were doing in preparation for the coming of the Messiah. That is why among the disciples of Yeshua, were some who were first disciples of John.

The text describes John as a prophet, very close to the description of Elijah the prophet, “John wore clothes made from camel’s hair, with a leather belt around his waist, and he ate locusts and wild honey.” His message was repentance and the coming of the Messiah: “After me comes One who is mightier than I am,” he proclaimed. “I’m not worthy to stoop down and untie the strap of His sandals! I immersed you with water, but He will immerse you in the Ruach ha-Kodesh” (Mark 1:1–8). That is a strange idea: The Ruach ha-Kodesh, (Holy Spirit in English). Of course, the Messiah will be immersed in water, but also in the Ruach, Isaiah said: “The Ruach of Hashem will rest upon Him, the Spirit of wisdom and insight, the Spirit of counsel and might, the Spirit of knowledge and of the fear of Hashem” (Isaiah 11:2). This spirit of wisdom, insight, counsel, might, knowledge, and fear of Hashem will be on Him, and according to John, not only on Him but also on everyone who believes in him as the Mashiach of Israel. What good news!