Nat Shaffir was born as Nathan Spitzer on a dairy farm in Transylvania, a region in central Romania. His father routinely provided the local priest with milk from the farm to give to congregants in need. However, one day in 1942, the priest showed up not to collect milk for the needy, but with soldiers and police officers, selling out the family to the Nazis.

“I’ve known you since you were a little child. I’ve known your parents,” Shaffir’s father pleaded with the clergyman and the officers. “Can’t you do something about ‘forgetting’ your order?”

The pleas were unsuccessful, the farm confiscated, and the Spitzer family, though being allowed to keep a horse and wagon to transport valuables, was relocated to a Jewish ghetto in the Socola neighborhood in nearby town of Iasi where a quarter loaf of bread every two days and five liters of kerosene was not uncommon. Most of the family that remained in Transylvania were ultimately deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau and Buchenwald by Hungarian gendamerie cooperating with the Nazis. Other family members perished from thirst and terrible conditions on the “Romanian Death Trains.”

Upon being rounded up for deportation to a labor camp, Nat’s father urged him to take care of his sisters.

“Now, I could have said, ‘OK dad, I’ll try,’ or ‘I’ll do my best,’” Shaffir said, less than 10 years old at the time. “I never did that. I said, ‘I will.’ I always kept my promise. That stood with me for a long time."

Russian forces liberated the Iasi ghetto in 1945. After the war, the family members who survived tried to reunite on the farm only to find the property had been divided between the priest who turned in the family, the officer who forcibly relocated the family to the Iasi ghetto, and the local mayor. Shaffir believes that 32 of his family members perished during the Holocaust.

The surviving family members attempted to leave Romania a couple times, but had exit visas denied which was a common problem for Jews seeking to leave post-war Romania. They finally negotiated with officials to board a cargo ship called Transylvania in 1950 setting sails for Haifa, Israel. In Israel, Shaffir served as a paratrooper in the Israeli army where he was shot in the knee, and in 1961, moved to Atlanta, Georgia where he started a business and eventually married his wife. The couple raised five children and have 12 grandchildren, all of whom are named after family members who perished in the Holocaust.

Today Nat and his bride reside near Silver Spring, Maryland where Nat runs marathons even at 81 years old post-knee replacement and volunteers with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

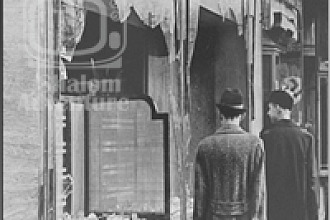

“The Holocaust could happen again,” Shaffir explained to Today. “Sometimes history repeats itself. We have to work very, very hard to make sure that atrocities like the Nazis have committed do not happen again… What concerns me is the anti-Semitism that’s going on in the United States. The thing that happened in Charlottesville could happen in other places.”

“Without these young people telling what happened, all our lives would have been wasted completely...Maybe we didn’t know during the ‘30s and ‘40s what these signs mean, but now we do know and we need to do something about it. We cannot remain silent. Even one person can make a difference, and one voice can make a difference.”

Shaffir then further elaborated at a 2018 Day of Remembrance event, “Despite all of the bad things that have happened, my parents instilled in us the idea that most people are good, and it’s important to try to help others.”

Written by Erin Parfet