Last week (October 29, 2013), a Taiwan steakhouse had its imported American beef tested after customers complained that it lacked flavor.

What did the restaurant owner discover?

The steaks they were serving contained a controversial banned drug additive called zilpaterol, marketed by Merck Pharmaceutical Company as Zilmax (rhymes with kill-whacks).

The restaurant immediately destroyed 450 pounds of meat after a food-testing lab confirmed the presence of zilpaterol.

How did this growth hormone get into the beef when it is banned? A problem for American consumers is that we are not wise enough to ban it here like Asian nations that import Texas beef.

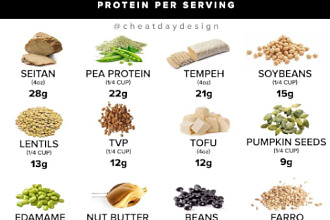

During the final two weeks of a cow's life while living in a feedlot being fattened before slaughter, zilpaterol can add as much as 30 pounds of lean muscle (meat) to the cow's body.

In 2012, Mother Jones magazine reported that a typical 1975 cow weighed 1,000 pounds. Today's zilpaterol-treated cows weigh 30 percent more, with the average animal tilting the scale at 1,300 pounds.

Critics of zilpaterol such as Temple Grandin have taken note of two things regarding zilpaterol use. First, in hot weather, zilpaterol-treated animals tend to go lame. Second, the flesh from treated animals is tasteless, as Taiwanese consumers have learned.

Most culled dairy cows are ground into chopped meat and sold to fast food burger franchises, were flavor is added in fried oil, ketchup, and special sauce.

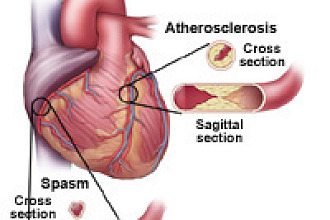

Zilpaterol is a beta-agonist, a kind of feed additive that is also given to American pigs. According to Wikipedia:

"...beta agonists usually have mild to moderate adverse effects, which includes anxiety, hypertension, increased heart rate and insomnia. Other side effects include headaches and essential tremor. Indications of hypoglycemia were also reported due to secretion of insulin in the body from activation."

In practice, feed-lot operators are instructed to discontinue zilpaterol use for three days before cows are sent to slaughter so that all residues of dangerous beta agonists leave the animal's muscle tissue. Tell that to Taiwanese beef eaters.

During the late summer of 2013, America's largest meat processor, Tyson Foods, observed that cattle treated with zilpaterol arrived at slaughterhouses having difficulty walking. Some cows were lame. Tyson blamed their behavior on zilpaterol and ceased "accepting" zilpaterol-treated animals.

In early November, USDA reports indicated that carcass weights of slaughtered animals have fallen dramatically. Merck is working closely with meat processors to resume acceptance of zilpaterol-treated animals. American consumers will not be told the outcome of Merck's behind-the-scenes negotiations. Nor will they be alerted to the consequences of consuming zilpaterol residues from animal flesh.

Most likely, today's Notmilk column will be the only opportunity for American consumers to learn about this new meat-eating risk.

"The more we pour the big machines, the fuel, the pesticides, the herbicides, the fertilizer and chemicals into farming, the more we knock out the mechanism that made it all work in the first place."

- David R. Brower

Originally found here

For more information, visit www.notmilk.com

Picture originally found here